- Home

Page 2

Page 2

The House of the Wolfings

The House of the Wolfings The Wood Beyond the World

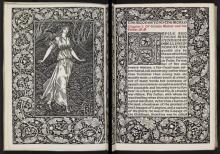

The Wood Beyond the World The Roots of the Mountains

The Roots of the Mountains The Well at the World's End: A Tale

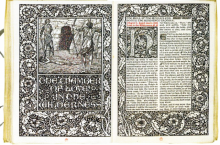

The Well at the World's End: A Tale Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair

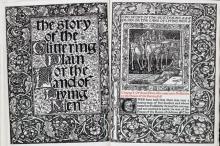

Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair The Story of the Glittering Plain

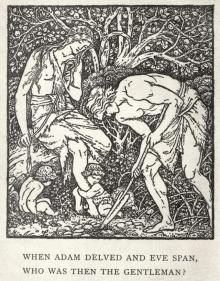

The Story of the Glittering Plain A Dream of John Ball; and, A King's Lesson

A Dream of John Ball; and, A King's Lesson News From Nowhere, Or, an Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters From a Utopian Romance

News From Nowhere, Or, an Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters From a Utopian Romance