- Home

- William Morris

The Roots of the Mountains Page 2

The Roots of the Mountains Read online

Page 2

CHAPTER I. OF BURGSTEAD AND ITS FOLK AND ITS NEIGHBOURS.

ONCE upon a time amidst the mountains and hills and falling streams of afair land there was a town or thorp in a certain valley. This waswell-nigh encompassed by a wall of sheer cliffs; toward the East and thegreat mountains they drew together till they went near to meet, and leftbut a narrow path on either side of a stony stream that came rattlingdown into the Dale: toward the river at that end the hills loweredsomewhat, though they still ended in sheer rocks; but up from it, andmore especially on the north side, they swelled into great shoulders ofland, then dipped a little, and rose again into the sides of huge fellsclad with pine-woods, and cleft here and there by deep ghylls: thenceagain they rose higher and steeper, and ever higher till they drew darkand naked out of the woods to meet the snow-fields and ice-rivers of thehigh mountains. But that was far away from the pass by the little riverinto the valley; and the said river was no drain from the snow-fieldswhite and thick with the grinding of the ice, but clear and bright wereits waters that came from wells amidst the bare rocky heaths.

The upper end of the valley, where it first began to open out from thepass, was rugged and broken by rocks and ridges of water-borne stones,but presently it smoothed itself into mere grassy swellings and knolls,and at last into a fair and fertile plain swelling up into a green wave,as it were, against the rock-wall which encompassed it on all sides savewhere the river came gushing out of the strait pass at the east end, andwhere at the west end it poured itself out of the Dale toward thelowlands and the plain of the great river.

Now the valley was some ten miles of our measure from that place of therocks and the stone-ridges, to where the faces of the hills drew somewhatanigh to the river again at the west, and then fell aback along the edgeof the great plain; like as when ye fare a-sailing past two nesses of ariver-mouth, and the main-sea lieth open before you.

Besides the river afore-mentioned, which men called the Weltering Water,there were other waters in the Dale. Near the eastern pass, entangled inthe rocky ground was a deep tarn full of cold springs and about two acresin measure, and therefrom ran a stream which fell into the WelteringWater amidst the grassy knolls. Black seemed the waters of that tarnwhich on one side washed the rocks-wall of the Dale; ugly and aweful itseemed to men, and none knew what lay beneath its waters save blackmis-shapen trouts that few cared to bring to net or angle: and it wascalled the Death-Tarn.

Other waters yet there were: here and there from the hills on both sides,but especially from the south side, came trickles of water that ran inpretty brooks down to the river; and some of these sprang bubbling upamidst the foot-mounds of the sheer-rocks; some had cleft a rugged andstrait way through them, and came tumbling down into the Dale at diverseheights from their faces. But on the north side about halfway down theDale, one stream somewhat bigger than the others, and dealing with softerground, had cleft for itself a wider way; and the folk had laboured thisway wider yet, till they had made them a road running north along thewest side of the stream. Sooth to say, except for the strait pass alongthe river at the eastern end, and the wider pass at the western, they hadno other way (save one of which a word anon) out of the Dale but such asmountain goats and bold cragsmen might take; and even of these but few.

This midway stream was called the Wildlake, and the way along itWildlake’s Way, because it came to them out of the wood, which on thatnorth side stretched away from nigh to the lip of the valley-wall up tothe pine woods and the high fells on the east and north, and down to theplain country on the west and south.

Now when the Weltering Water came out of the rocky tangle near the pass,it was turned aside by the ground till it swung right up to the feet ofthe Southern crags; then it turned and slowly bent round again northward,and at last fairly doubled back on itself before it turned again to runwestward; so that when, after its second double, it had come to flowingsoftly westward under the northern crags, it had cast two thirds of agirdle round about a space of land a little below the grassy knolls andtofts aforesaid; and there in that fair space between the folds of theWeltering Water stood the Thorp whereof the tale hath told.

The men thereof had widened and deepened the Weltering Water about them,and had bridged it over to the plain meads; and athwart the throat of thespace left clear by the water they had built them a strong wall thoughnot very high, with a gate amidst and a tower on either side thereof.Moreover, on the face of the cliff which was but a stone’s throw from thegate they had made them stairs and ladders to go up by; and on a knollnigh the brow had built a watch-tower of stone strong and great, lest warshould come into the land from over the hills. That tower was ancient,and therefrom the Thorp had its name and the whole valley also; and itwas called Burgstead in Burgdale.

So long as the Weltering Water ran straight along by the northern cliffsafter it had left Burgstead, betwixt the water and the cliffs was a wideflat way fashioned by man’s hand. Thus was the water again a gooddefence to the Thorp, for it ran slow and deep there, and there was noother ground betwixt it and the cliffs save that road, which was easy tobar across so that no foemen might pass without battle, and this road wascalled the Portway. For a long mile the river ran under the northerncliffs, and then turned into the midst of the Dale, and went its waywestward a broad stream winding in gentle laps and folds here and theredown to the out-gate of the Dale. But the Portway held on stillunderneath the rock-wall, till the sheer-rocks grew somewhat broken, andwere cumbered with certain screes, and at last the wayfarer came upon thebreak in them, and the ghyll through which ran the Wildlake withWildlake’s Way beside it, but the Portway still went on all down the Daleand away to the Plain-country.

That road in the ghyll, which was neither wide nor smooth, the wayfarerinto the wood must follow, till it lifted itself out of the ghyll, andleft the Wildlake coming rattling down by many steps from the east; andnow the way went straight north through the woodland, ever mountinghigher, (because the whole set of the land was toward the high fells,)but not in any cleft or ghyll. The wood itself thereabout was thick, ablended growth of diverse kinds of trees, but most of oak and ash; lightand air enough came through their boughs to suffer the holly and brambleand eglantine and other small wood to grow together into thickets, whichno man could pass without hewing a way. But before it is told wheretoWildlake’s Way led, it must be said that on the east side of the ghyll,where it first began just over the Portway, the hill’s brow was clear ofwood for a certain space, and there, overlooking all the Dale, was theMote-stead of the Dalesmen, marked out by a great ring of stones, amidstof which was the mound for the Judges and the Altar of the Gods beforeit. And this was the holy place of the men of the Dale and of other folkwhereof the tale shall now tell.

For when Wildlake’s Way had gone some three miles from the Mote-stead,the trees began to thin, and presently afterwards was a clearing and thedwellings of men, built of timber as may well be thought. These houseswere neither rich nor great, nor was the folk a mighty folk, because theywere but a few, albeit body by body they were stout carles enough. Theyhad not affinity with the Dalesmen, and did not wed with them, yet it isto be deemed that they were somewhat akin to them. To be short, thoughthey were freemen, yet as regards the Dalesmen were they well-nigh theirservants; for they were but poor in goods, and had to lean upon themsomewhat. No tillage they had among those high trees; and of beastsnought save some flocks of goats and a few asses. Hunters they were, andcharcoal-burners, and therein the deftest of men, and they could shootwell in the bow withal: so they trucked their charcoal and their smokedvenison and their peltries with the Dalesmen for wheat and wine andweapons and weed; and the Dalesmen gave them main good pennyworths, asmen who had abundance wherewith to uphold their kinsmen, though they werebut far-away kin. Stout hands had these Woodlanders and true hearts asany; but they were few-spoken and to those that needed them not somewhatsurly of speech and grim of visage: brown-skinned they were, butlight-haired; well-eyed, with but little red in their cheeks: t

heir womenwere not very fair, for they toiled like the men, or more. They werethought to be wiser than most men in foreseeing things to come. Theywere much given to spells, and songs of wizardry, and were very mindfulof the old story-lays, wherein they were far more wordy than in theirdaily speech. Much skill had they in runes, and were exceeding deft inscoring them on treen bowls, and on staves, and door-posts and roof-beamsand standing-beds and such like things. Many a day when the snow wasdrifting over their roofs, and hanging heavy on the tree-boughs, and thewind was roaring through the trees aloft and rattling about the closethicket, when the boughs were clattering in the wind, and crashing downbeneath the weight of the gathering freezing snow, when all beasts andmen lay close in their lairs, would they sit long hours about thehouse-fire with the knife or the gouge in hand, with the timber twixttheir knees and the whetstone beside them, hearkening to some tale of oldtimes and the days when their banner was abroad in the world; and theythe while wheedling into growth out of the tough wood knots and blossomsand leaves and the images of beasts and warriors and women.

They were called nought save the Woodland-Carles in that day, though timehad been when they had borne a nobler name: and their abode was calledCarlstead. Shortly, for all they had and all they had not, for all theywere and all they were not, they were well-beloved by their friends andfeared by their foes.

Now when Wildlake’s Way was gotten to Carlstead, there was an end of ittoward the north; though beyond it in a right line the wood was thinner,because of the hewing of the Carles. But the road itself turned west atonce and went on through the wood, till some four miles further it firstthinned and then ceased altogether, the ground going down-hill all theway: for this was the lower flank of the first great upheaval toward thehigh mountains. But presently, after the wood was ended, the land brokeinto swelling downs and winding dales of no great height or depth, with afew scattered trees about the hillsides, mostly thorns or scrubby oaks,gnarled and bent and kept down by the western wind: here and there alsowere yew-trees, and whiles the hillsides would be grown over withbox-wood, but none very great; and often juniper grew abundantly. Thisthen was the country of the Shepherds, who were friends both of theDalesmen and the Woodlanders. They dwelt not in any fenced town orthorp, but their homesteads were scattered about as was handy for waterand shelter. Nevertheless they had their own stronghold; for amidmost oftheir country, on the highest of a certain down above a bottom where awillowy stream winded, was a great earthwork: the walls thereof were highand clean and overlapping at the entering in, and amidst of it was a deepwell of water, so that it was a very defensible place: and thereto wouldthey drive their flocks and herds when war was in the land, for noughtbut a very great host might win it; and this stronghold they calledGreenbury.

These Shepherd-Folk were strong and tall like the Woodlanders, for theywere partly of the same blood, but burnt they were both ruddy and brown:they were of more words than the Woodlanders but yet not many-worded.They knew well all those old story-lays, (and this partly by theminstrelsy of the Woodlanders,) but they had scant skill in wizardry, andwould send for the Woodlanders, both men and women, to do whatso theyneeded therein. They were very hale and long-lived, whereas they dweltin clear bright air, and they mostly went light-clad even in the winter,so strong and merry were they. They wedded with the Woodlanders and theDalesmen both; at least certain houses of them did so. They grew nocorn; nought but a few pot-herbs, but had their meal of the Dalesmen; andin the summer they drave some of their milch-kine into the Dale for theabundance of grass there; whereas their own hills and bents and windingvalleys were not plenteously watered, except here and there as in thebottom under Greenbury. No swine they had, and but few horses, but ofsheep very many, and of the best both for their flesh and their wool.Yet were they nought so deft craftsmen at the loom as were the Dalesmen,and their women were not very eager at the weaving, though they loathednot the spindle and rock. Shortly, they were merry folk well-beloved ofthe Dalesmen, quick to wrath, though it abode not long with them; notvery curious in their houses and halls, which were but little, and weredecked mostly with the handiwork of the Woodland-Carles their guests; whowhen they were abiding with them, would oft stand long hours nose tobeam, scoring and nicking and hammering, answering no word spoken to thembut with aye or no, desiring nought save the endurance of the daylight.Moreover, this shepherd-folk heeded not gay raiment over-much, butcommonly went clad in white woollen or sheep-brown weed.

But beyond this shepherd-folk were more downs and more, scantily peopled,and that after a while by folk with whom they had no kinship or affinity,and who were at whiles their foes. Yet was there no enduring enmitybetween them; and ever after war and battle came peace; and allblood-wites were duly paid and no long feud followed: nor were theDalesmen and the Woodlanders always in these wars, though at whiles theywere. Thus then it fared with these people.

But now that we have told of the folks with whom the Dalesmen hadkinship, affinity, and friendship, tell we of their chief abode,Burgstead to wit, and of its fashion. As hath been told, it lay upon theland made nigh into an isle by the folds of the Weltering Water towardsthe uppermost end of the Dale; and it was warded by the deep water, andby the wall aforesaid with its towers. Now the Dale at its widest, towit where Wildlake fell into it, was but nine furlongs over, but atBurgstead it was far narrower; so that betwixt the wall and the wanderingstream there was but a space of fifty acres, and therein lay Burgstead ina space of the shape of a sword-pommel: and the houses of the kinshipslay about it, amidst of gardens and orchards, but little ordered intostreets and lanes, save that a way went clean through everything from thetower-warded gate to the bridge over the Water, which was warded by twoother towers on its hither side.

As to the houses, they were some bigger, some smaller, as the housematesneeded. Some were old, but not very old, save two only, and some quitenew, but of these there were not many: they were all built fairly ofstone and lime, with much fair and curious carved work of knots andbeasts and men round about the doors; or whiles a wale of such-like workall along the house-front. For as deft as were the Woodlanders withknife and gouge on the oaken beams, even so deft were the Dalesmen withmallet and chisel on the face of the hewn stone; and this was a greatpastime about the Thorp. Within these houses had but a hall and solar,with shut-beds out from the hall on one side or two, with whatso ofkitchen and buttery and out-bower men deemed handy. Many men dwelt ineach house, either kinsfolk, or such as were joined to the kindred.

Near to the gate of Burgstead in that street aforesaid and facing eastwas the biggest house of the Thorp; it was one of the two abovesaid whichwere older than any other. Its door-posts and the lintel of the doorwere carved with knots and twining stems fairer than other houses of thatstead; and on the wall beside the door carved over many stones was animage wrought in the likeness of a man with a wide face, which wasterrible to behold, although it smiled: he bore a bent bow in his handwith an arrow fitted to its string, and about the head of him was a ringof rays like the beams of the sun, and at his feet was a dragon, whichhad crept, as it were, from amidst of the blossomed knots of thedoor-post wherewith the tail of him was yet entwined. And this head withthe ring of rays about it was wrought into the adornment of that house,both within and without, in many other places, but on never another houseof the Dale; and it was called the House of the Face. Thereof hath thetale much to tell hereafter, but as now it goeth on to tell of the waysof life of the Dalesmen.

In Burgstead was no Mote-hall or Town-house or Church, such as we wot ofin these days; and their market-place was wheresoever any might choose topitch a booth: but for the most part this was done in the wide streetbetwixt the gate and the bridge. As to a meeting-place, were there anysmall matters between man and man, these would the Alderman or one of theWardens deal with, sitting in Court with the neighbours on the wide spacejust outside the Gate: but if it were to do with greater matters, such asgreat manslayings and blood-wites, or the making of war or ending of it,

or the choosing of the Alderman and the Wardens, such matters must be putoff to the Folk-mote, which could but be held in the place aforesaidwhere was the Doom-ring and the Altar of the Gods; and at that Folk-moteboth the Shepherd-Folk and the Woodland-Carles foregathered with theDalesmen, and duly said their say. There also they held their greatcasts and made offerings to the Gods for the Fruitfulness of the Year,the ingathering of the increase, and in Memory of their Forefathers.Natheless at Yule-tide also they feasted from house to house to be gladwith the rest of Midwinter, and many a cup drank at those feasts to thememory of the fathers, and the days when the world was wider to them, andtheir banners fared far afield.

But besides these dwellings of men in the field between the wall and thewater, there were homesteads up and down the Dale whereso men found iteasy and pleasant to dwell: their halls were built of much the samefashion as those within the Thorp; but many had a high garth-wall castabout them, so that they might make a stout defence in their own housesif war came into the Dale.

As to their work afield; in many places the Dale was fair with growth oftrees, and especially were there long groves of sweet chestnut standingon the grass, of the fruit whereof the folk had much gain. Also on thesouth side nigh to the western end was a wood or two of yew-trees verygreat and old, whence they gat them bow-staves, for the Dalesmen alsoshot well in the bow. Much wheat and rye they raised in the Dale, andespecially at the nether end thereof. Apples and pears and cherries andplums they had in plenty; of which trees, some grew about the borders ofthe acres, some in the gardens of the Thorp and the homesteads. On theslopes that had grown from the breaking down here and there of theNorthern cliffs, and which faced the South and the Sun’s burning, wererows of goodly vines, whereof the folk made them enough and to spare ofstrong wine both white and red.

As to their beasts; swine they had a many, but not many sheep, sinceherein they trusted to their trucking with their friends the Shepherds;they had horses, and yet but a few, for they were stout in going afoot;and, had they a journey to make with women big with babes, or withchildren or outworn elders, they would yoke their oxen to their wains,and go fair and softly whither they would. But the said oxen and alltheir neat were exceeding big and fair, far other than the little beastsof the Shepherd-Folk; they were either dun of colour, or white with blackhorns (and those very great) and black tail-tufts and ear-tips. Assesthey had, and mules for the paths of the mountains to the east; geese andhens enough, and dogs not a few, great hounds stronger than wolves,sharp-nosed, long-jawed, dun of colour, shag-haired.

As to their wares; they were very deft weavers of wool and flax, and madea shift to dye the thrums in fair colours; since both woad and maddercame to them good cheap by means of the merchants of the plain country,and of greening weeds was abundance at hand. Good smiths they were inall the metals: they washed somewhat of gold out of the sands of theWeltering Water, and copper and tin they fetched from the rocks of theeastern mountains; but of silver they saw little, and iron they must buyof the merchants of the plain, who came to them twice in the year, to witin the spring and the late autumn just before the snows. Their waresthey bought with wool spun and in the fleece, and fine cloth, and skinsof wine and young neat both steers and heifers, and wrought copper bowls,and gold and copper by weight, for they had no stamped money. And theyguested these merchants well, for they loved them, because of the talesthey told them of the Plain and its cities, and the manslayings therein,and the fall of Kings and Dukes, and the uprising of Captains.

Thus then lived this folk in much plenty and ease of life, though notdelicately nor desiring things out of measure. They wrought with theirhands and wearied themselves; and they rested from their toil and feastedand were merry: to-morrow was not a burden to them, nor yesterday a thingwhich they would fain forget: life shamed them not, nor did death makethem afraid.

As for the Dale wherein they dwelt, it was indeed most fair and lovely,and they deemed it the Blessing of the Earth, and they trod its flowerygrass beside its rippled streams amidst its green tree-boughs proudly andjoyfully with goodly bodies and merry hearts.

The House of the Wolfings

The House of the Wolfings The Wood Beyond the World

The Wood Beyond the World The Roots of the Mountains

The Roots of the Mountains The Well at the World's End: A Tale

The Well at the World's End: A Tale Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair

Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair The Story of the Glittering Plain

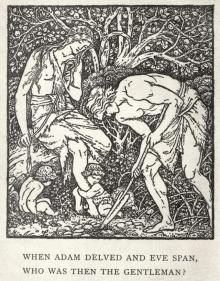

The Story of the Glittering Plain A Dream of John Ball; and, A King's Lesson

A Dream of John Ball; and, A King's Lesson News From Nowhere, Or, an Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters From a Utopian Romance

News From Nowhere, Or, an Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters From a Utopian Romance